Ron MacFarlane, a logging contractor on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast, counts himself lucky. His eight-person crew is currently working, felling second-growth Douglas fir, a small reprieve in an industry rapidly spiraling into uncertainty. But the work, secured only until March, feels increasingly precarious.

The broader forestry landscape paints a grim picture. Conditions have “definitely gone downhill” in the last two years, MacFarlane admits, a sentiment echoed throughout the industry. He dreams of consistent, ten-month contracts, enough to offer stability to his employees, but lately, he’s been “stumbling over the same amount of wood” as competitors, all vying for a shrinking resource.

Last year revealed the depth of the crisis. Despite an annual allowable harvest of 45 million cubic metres, companies managed to log only 32 million. Mill closures, like the devastating shutdown of Domtar’s Crofton pulp mill, became commonplace, leaving communities reeling and workers facing an uncertain future.

Peter Lister, executive director of the Truck Loggers Association, has spent over 35 years in the forest industry and has never witnessed such a dire situation. He describes the industry as “on the edge of collapse,” hampered by agonizingly slow permitting processes that prevent access to available timber.

While acknowledging external pressures like crippling 45% U.S. softwood lumber duties, Lister implores the provincial Forest Minister to address the issues within his control. The call for action is urgent, a desperate plea to prevent further devastation.

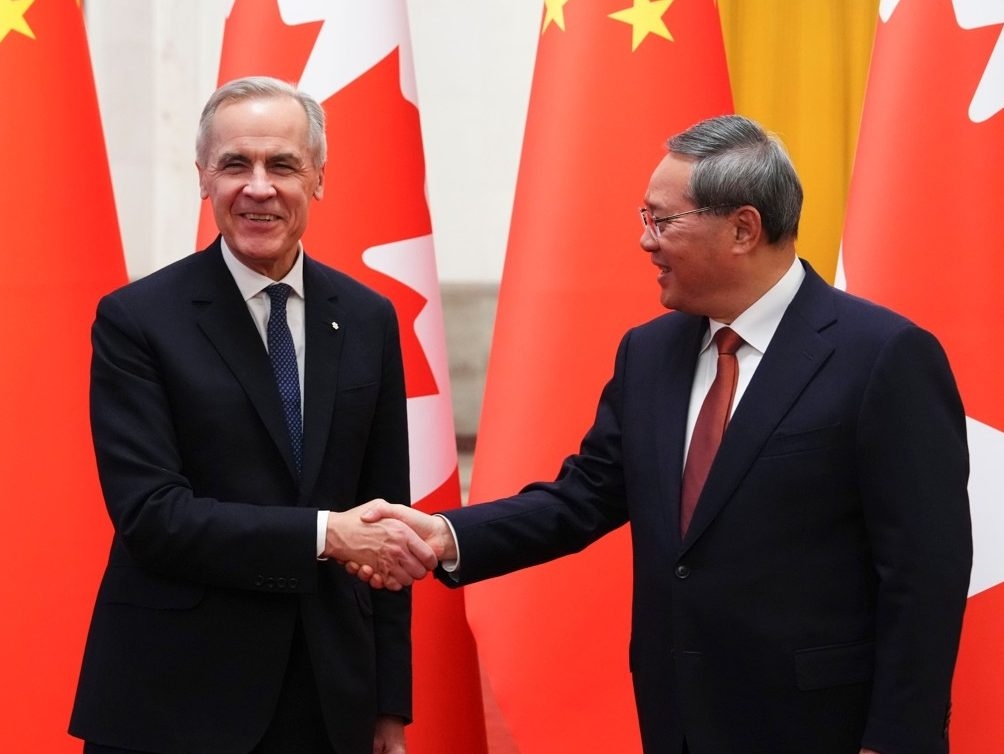

Forest Minister Ravi Parmar recently announced a new agreement with China, aiming to integrate modern wood construction techniques into their building sector. He envisions this partnership bringing “more jobs, more certainty and more stability” to British Columbia’s forestry workers.

Parmar’s long-term solution centers on a shift from individual cut-block permits to area-based permitting, guided by comprehensive land-use plans developed collaboratively with industry, First Nations, and the government. He boldly suggests a future “where we have no need for cutting permits in forestry” altogether.

However, Parmar acknowledges his first year in office hasn’t yielded all the desired results, candidly admitting an “incomplete” grade against his initial mandate. He anticipates another “tough year” ahead, but remains committed to a necessary, albeit challenging, transformation of the industry.

Lister responds with cautious optimism, reserving judgment until the details of Parmar’s proposed plans are revealed. While acknowledging a growing understanding of the industry’s challenges, he emphasizes the need for concrete action.

Forest-management executive John Mohammed is far less sanguine. He argues that Parmar’s focus on long-term plans overlooks the immediate needs of an industry suffocating under bureaucratic delays. He points to a declining harvest rate during Parmar’s tenure as evidence of a worsening situation.

Mohammed urges the Minister to consider immediate, impactful measures, such as lowering stumpage rates – the fees charged for harvested trees – to stimulate economic viability. The message is clear: the industry is on the brink, and requires swift, decisive action to safeguard jobs and prevent further collapse.

The future of British Columbia’s forestry sector hangs in the balance, a complex web of economic pressures, political decisions, and the livelihoods of countless families.